Feminism dreams of a multitude of languages

Listen to the series Science beyond the suit (in Slovene):

E2 Locked Doors

E6 Unfiltered

Tea Hvala is the guest of Episode 5 of this podcast.

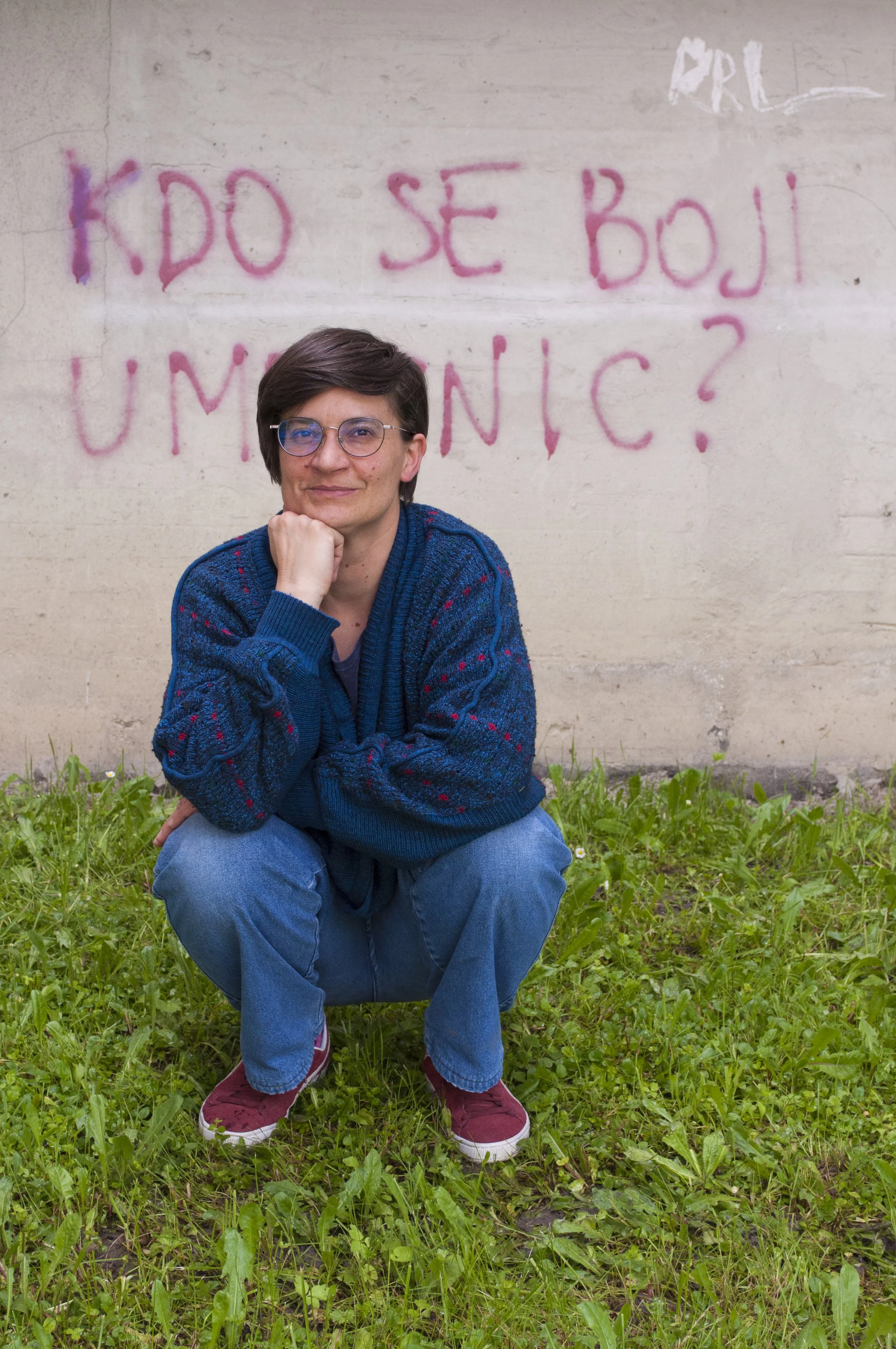

Tea Hvala. Photo: Janja Golob

author:

Maja Čakarić

editor:

Klara Škrinjar

At the intersection of feminist thought and science fiction works Tea Hvala, author, translator, and editor of texts that explore the possibilities of social imagination in the genre of science fiction. She studied comparative literature and cultural sociology, then earned a master's degree in gender anthropology.

She became more intensely interested in science fiction when she encountered American authors who began introducing feminist ideas into the genre during the second wave of Western feminism in the late 1960s. iIn her thesis she wrote about authors such as Ursula K. Le Guin, Joanna Russ, Marge Piercy, Samuel R. Delany, Theodore Sturgeon, Octavia E. Butler, and James Tiptree Jr. (pseudonym of Alice Sheldon). Feminist science fiction has accompanied her ever since as a reader, translator, and writer.

In addition to her individual creative work, she has organised group writing workshops on feminist and queer science fiction, called Worlds of Others, for several years in which science fiction served as a space for collective reflection, imagination, and exploration of alternative social orders.

Traditional science fiction focused on technology, world conquest, physical problems, i.e., hard science. It often had imperialist, colonial undertones. Then, in the 1960s, all this was turned upside down. Feminist authors brought anthropology, sociology, and psychology to the fore. What actually happened at that time, and how important is this shift for understanding science? And how important is it to consider that technological progress without social progress does not mean much?

In the Anglo-American world, this shift was directly linked to the rise of the second wave of the feminist movement whose more radical aspects, such as the demand for the abolition of the nuclear family and the liberation of children, are largely forgotten today. At that time, female authors appeared for the first time in science fiction, which had previously been considered an exclusively male genre: first white women, some under male pseudonyms, and gradually others, such as black and lesbian writers. We also encounter black gay authors such as Samuel Delany for the first time.

The protagonists of their works are not white, Western, heterosexual, physically able-bodied middle-class men, but non-normative and marginalised subjects. They appropriated the language that had previously marked them as different and verbalised the world from their perspective. This is the most noticeable difference between so-called "hard" and "soft" SF, whereby this schematic division reflects both the real, traditional gender division of labor and the expectation that male writers will devote themselves to the natural sciences and female writers to the social sciences of fictional worlds. The expectations that readers, critics, and others invest in the supposed difference between male and female writing were turned upside down in American SF circles in 1976 by the revelation that James Tiptree Jr. was the pseudonym of the writer Alice Sheldon. Until then, "his" work had been praised as "unmistakably masculine." Why? Because Sheldon wrote about universal issues—life and death, courage and suffering.

The shift you mentioned in your question is also noticeable in the 1960s. If "hard" or technicist SF was based on expansionism, colonial conquest, and appropriation of Others (worlds, subjectivities, etc.), "soft" or socially oriented SF brought to the fore the dichotomies that make such differentiation possible in the first place. Not only the hierarchical division into two sexes, but also all other dichotomies that are supposed to define the human in relation to the animal, the machine, and the extraterrestrial.

These dichotomies also include the division between "hard" and "soft" SF. As already mentioned, the boundary between the two is not always clear, especially when it comes to the relationship to technological progress. Even the authors of hard SF warned against blind faith in technological development, as it was quite clear during the Cold War that this – without ethical restrictions – could lead to disaster. But technological progress meant much more than that. Feminists saw the development of reproductive technologies, such as artificial insemination and contraception, as a promise of liberation from forced reproduction and motherhood. In this sense, feminist SF placed technological development within the context of social development, linking it to intimate and political power relations and the question of justice.

Can SF, throughout its history, be understood as a laboratory for the humanities and social sciences, where we test social models that are not yet possible in reality, thereby expanding the boundaries of what is understood as "natural" or "scientific fact"?

Yes, we could say that. With the caveat that some models are not feasible. I am referring to the utopian depictions of paradise, where milk and honey flow, which offer comfort to writers and readers, especially in circumstances that are far from paradise. If we understand SF as part of a utopian literary tradition that dates back at least to the Middle Ages, and if we take into account that Thomas More's coinage u-topos means "a place that does not exist," then it is even true that fictional social orders are de facto unfeasible. This does not mean, of course, that they are not inspiring. They can certainly contribute to the exploration and creation of "utopistics," as historian and sociologist Immanuel Wallerstein called the humanistic, i.e., scientific search for historical alternatives or real possibilities for social development.

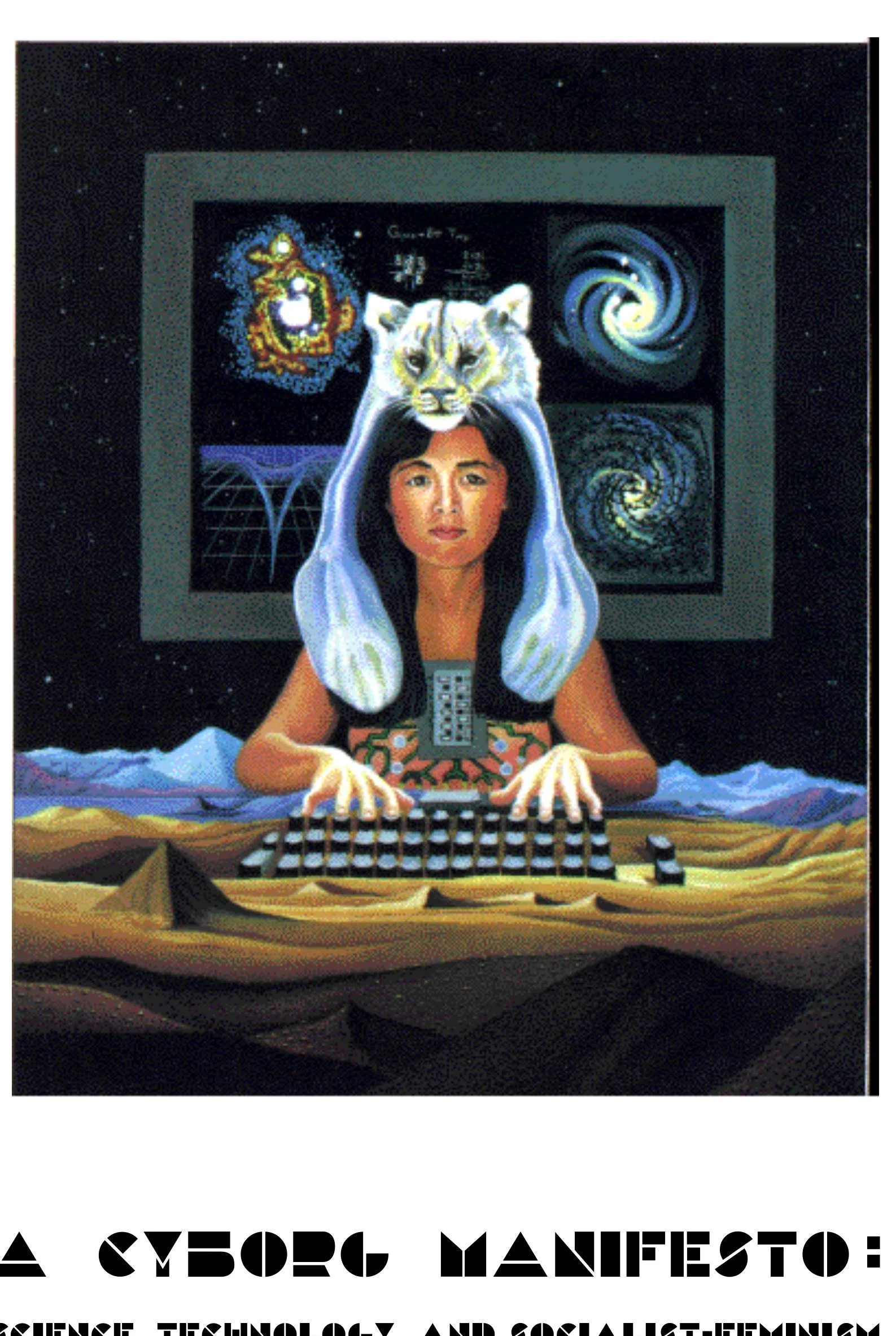

In the mid-1980s, American science historian Donna Haraway was enthusiastic about feminist SF. In her Cyborg Manifesto, she wrote that feminism does not dream of a single, common language, but of a "mighty heteroglossia of unbelievers"; of a multitude of subjectivities and languages that would "strike fear into the bones of the super-saviors of the new right." In short, she understood feminist science fiction as a laboratory for conducting thought experiments which, as you yourself said, expand the field of the possible and the imaginable because we must first imagine the change we want to bring about.

But again, we probably don't want anti-utopian societies such as the one in Margaret Atwood's The Handmaid's Tale, to become a reality. If for no other reason than because they already have. It is well known that when writing this book, Atwood followed the rule that she would not include anything that had not already happened in human history – in this or that totalitarian state, military regime, or religious community.

Can we say that feminist science fiction literature has done what science (biology) has long failed to do, namely show that nature is much more diverse than textbooks claim?

We can, but mainly because artistic creation has immeasurably greater freedom than scientific research. We take artists at their word otherwise we would not be able to enjoy their works. We do not demand verifiable facts and solid evidence from them but instead we expect internal consistency of the fictional worlds they create.

It is true that science fiction authors have already imagined all possible sexual arrangements, from "ambisexuality" in Ursula K. Le Guin's novel The Left Hand of Darkness to the immense proliferation of sexual identities in Samuel Delany's novel Triton. However, SF does not exist in a vacuum. The aforementioned books were written at a specific time and place, which is why, for example, The Left Hand of Darkness sounds heteronormative today even though it tried to avoid this. Nevertheless, I believe that some works have stood the test of time, such as Octavia E. Butler's Xenogenesis trilogy better known under the more marketable title Lilith's Brood. In the final book, Imago (1989), Butler engages in a dialogue with the idea of unlimited arbitrariness in identity definitions and warns that this leads to a dead end if the individual is not embedded in a social network of less chaotic and changeable forms of life than their own.

In the past, the avant-garde and science fiction often celebrated technology as the solution to everything. Feminist science fiction, however, often points out that technology reinforces oppression in patriarchal societies. How does this apply today? Does feminist SF help us understand why "more science" (AI, genetic engineering) alone will not save the world if we do not simultaneously change the social relations that these authors write about?

It certainly helps, with many works pointing not only to the patriarchal framework but also to the capitalist, profit-driven framework that neglects ethical standards or consideration of the risks associated with specific uses of a given technology. In other words, does the fact that we know how to do something, such as make new weapons, necessarily mean that we must do it, if we know that it will only bring suffering or death to the vast majority of people?

In the case of AI and genome editing, ethical considerations are accompanied by philosophical questions about their consequences for humans as a species, about what defines humanity in the first place. A topic explored by Philip K. Dick, an exceptional writer whom we know today indirectly through numerous film adaptations of his novels and stories—including the proto-feminist story "Human Is."

Science fiction is full of monsters and aliens whom humans oppose. Feminist authors, however, have often taken on the perspective of these "others," inhabiting them and blurring the boundaries between us and them. What does this changed perspective reveal? And does literature hold up a mirror to us and try to show that what society, and even science, labels as unnatural and alien is not a threat but a form of existence that should not be pigeonholed? And how liberating is this feeling in your eyes?

People who are neglected, discriminated against, or even ostracised in this society often identify with the character of the monster. To avoid generalising, I would answer this question with an example. I would return to Octavia Butler, an American black writer who, unfortunately, did not live to see her works become popular. In her trilogy Xenogenesis, the extraterrestrial people of Oankali kidnap or rescue a handful of Earthlings who survived the Third World War—a nuclear catastrophe. The Oankali are repulsive, giant snakes, worms, snails, and octopuses all at once, with a "command" in their genes that they must constantly change. The story is told by Lilith Iyapo, a white woman who lost everything in the war—including her husband and child. While her Nigerian surname evokes memories of the slave trade, her name recalls the first wife of the biblical Adam, who was expelled from paradise for her disobedience and gave birth to a brood of monstrous children with demons. The Oankali expect Lilith to mate with them and prepare their monstrous offspring for life on a restored Earth. Lilith initially reacts with hostility to the Oankali plan but then accepts her task, as she has no choice as a slave. She gives birth to a child who is a "genetic construct" and thus also accepts the Oankali alienness, knowing that this is a condition for survival and resistance to Oankali colonialism.

When Lilith asks the Oankali why they chose humans for "genetic exchange," they reply that it is because this species is "specialised in extinction and stagnation" and because we are contradictory: highly intelligent, yet investing all our intelligence in establishing hierarchies. When she asks if they intend to improve us, the Oankali reply that humanity will not be better after the exchange, "just different. Not quite like you. A little like us." So not the same, not different, not familiar, not foreign, but something in between.

The production of podcasts and other content was financially supported by ARIS through the 2025 Public Call for the (Co)financing of Science Popularization Activities.